*All quotations, unless otherwise noted, are taken from the text.

Because slasher victims are saprophagous organisms whose screen-time subsists on decay (when one of them dies, their absence is absorbed by the next victim’s presence), a slasher film can only begin if the past has decayed into myth. In 1958, two Camp Crystal Lake counselors were murdered at work and the camp was closed. We’re wrong to refer to ghosts as the dead when their bodies are a language of acousmatic sound. Crushed leaves and creaking doors. Like “irritating, causeless pains.” The speech of townsfolk superstition. “The past extends, coeval with the present.” Our ghosts are very much alive. Twenty-odd years later, Camp Crystal Lake reopens. Annie, a new camp counselor, is told the place is haunted, that it has a death curse, but she doesn’t let that bother her. It’s 1979, and the past is just a myth. She’ll be the first to die.

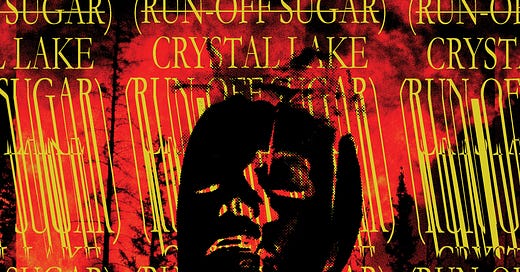

(Run-Off Sugar).

The struckthrough parenthetical is the book’s first victim, and like every slasher victim it’s death breeds a replacement.

Crystal Lake.

Where bodies are walking graves, each interring their duplicate who died before them. A never ending sequence of murder and renewal. “Duplicate, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat, repeat.”

//

The film critic Robin Wood famously read horror movies as being structured around an ideological principle that he identified as the “return of the repressed.” The “aberrant” desires that have been successfully sublimated into the white, heterosexist nuclear family are re-presented in the form of a monster. When we see from the monster’s perspective – Norman Bates spying on Marion Crane, baby Adrian looking up from its bassinet at Rosemary Woodhouse – we are shown that the membrane separating normal from abnormal has frayed. That the membrane was only ever a thin disguise of embodiment in the first place. A “self remade around the wound.” But the return of the repressed is an untenable framework when applied to post-Halloween slashers. Although the slasher might literally exist outside of society – in woods and ramshackle towns and in dreams – they do not represent that which exists outside of society. The slasher, in their systematic execution of those they’ve deemed deserving of death according to a code of prejudice, represents the law.

More and more dome cameras look like open pomegranates. Surveillance is intended to capture you in such a way that if you escape you’ll be returned to your captor.

The point-of-view of the law, and the implementation of the law, are omnipresent. If Jason Voorhees is silhouetted in the woods he’s also watching you from underneath the lake. He killed two teenagers making love in a tent while flattening the tires of your Winnebago. “The law evades responsibility for its incongruencies.” A single murder is a tragedy. A multitude of murders is an institution. A franchise. “Homicide for Homeostasis.” The maintenance of the law depends on labeling certain lives as contraband, so that other lives may benefit from those lives’ confiscation. Our economy stills launders fortunes made from slavery. Our railroad ties are gravemarkers of genocide. In a world that “won’t stop ending,” where cities aspirate the ocean, and the sky suffers a pleuritic sun, desperation has been judged a murderable offense.

The victims in these movies are primarily white, and as such, they don’t see the slasher as the law, but as that which redounds their faith in the law. They call the police. As if the law prevents the law from murdering more than it otherwise would. When, in fact, “the killers tend to keep each other busy” justifying each other’s crimes.

Logan Berry and Mike Corrao, the book’s co-designer, countervail the law by creating a text that operates according to a sort of ontological synesthesia. Identities are reconstituted through their senses and evade detection. On a material level, (Run-Off Sugar) Crystal Lake is a book with a film being screened through its pages. Landscapes are blemished by a virus of light. Like snowfall from a cystic sky. The book/film’s inhabitants are mutable. “We revise the relationship between the wildflowers and dura mater.” Reality bickers with its simulation and we occupy what’s left unspoken. “Hallucinations as a Season.” Becoming and disappearing simultaneously. “Inside-out – an escape artist.”